[atlasvoice]

A good farm dog was valuable and greatly appreciated, both as a loyal friend and an indispensable co-worker. “Every good farmer had to have a good farm dog,” informed one anonymous man, interviewed in this 21st century about his 20th century boyhood in southeastern Houston County. He fondly remembered a “beautiful” collie named King, who accompanied him each afternoon while performing one of his chores – bringing back the cows from the pasture.

King would lead the lad to wherever the cows were grazing and once heading back home, “King was always there to nip any stray in the heels and get her back in line with the group. He was such a loyal, helpful friend, always on the job.” And jobs began early; the boy was rousted out of bed by his father at 4:45 every morning.

A four-footed friend with hooves could also help. After his dad had purchased another farm about a mile and half away from the homeplace, his horse-raising uncle took pity on the boy who then had to walk to fetch the cows from the more distant pasture as well. His uncle gave him a Shetland pony for transportation.

“At first, the pony was boss, not me,” he lamented. “He would look for a low-hanging limb, and drag me off his back. I complained to my uncle, and he said, “We’ll fix that!” He got me a bridle with a wire bit and then I could make the pony mind me.”

In the mid-1800s in Houston County, most of the earliest white settlers were farmers. And wheat was the first cash crop. The earliest harvesting involved cutting the wheat by hand with a scythe and later with a horse-drawn mechanical reaper before being raked by hand.

Improvement came with the reaper-binder, which both reaped the crop and bound it into sheaves, which were allowed to dry before being picked up and taken to the thresher.

The threshing machine separated the grain or wheat seeds from the stalks.

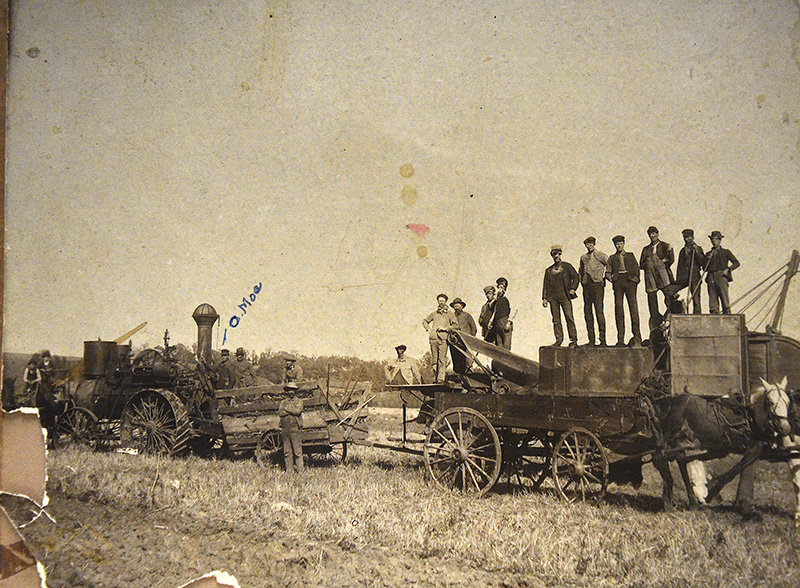

The earliest threshers were horse-powered, soon to be replaced by steam engine-powered threshers. Steam engine threshers were available by 1860, but there were few in southeastern Houston County until 1900. But they were both expensive and labor intensive. Therefore, some farmers grouped together, forming co-ops to own the machine. Other farmers cut their own grain and then paid an owner to bring a thresher to his farm.

By the late 1930s into the early 1940s, tractor-powered threshing was replacing the steam engines. The combine harvester would later replace the binder and thresher, accomplishing both operations with one machine. In the Winnebago Valley, there were reports that combines were replacing threshing as early as the late 1950s, while tractor-threshing continued in some areas until about 1970.

“My first job threshing job was to run the water tank wagon to supply the steam engine with water. I was a very proud 10 year old,” recalled one anonymous Houston County man. “The threshing crews were a big part of life. They started early. It was a big social event.”

Many trips were made from the fields to the threshing machine. The men pitched bundles up onto the wagons, which were driven by the children. But those children were not allowed near the threshing machine because of the dangerous belt. It required at least 10 people working at the same time to keep the machine going.

Despite machinery, there was still plenty of hand labor as described by one former participant: “Grain would be cut with the binder, and then they shocked it up. Earlier, it was stacked before it was threshed. Later they hauled it in bundles and then threshed it.” Barley was especially difficult to shock.

At dinnertime, the men all ate first and then rested in a shady spot while the women and children were eating. The threshing rig would head up Winnebago Valley to other farms. The tanker traveled, too, but would stop at a spring if it needed to be refilled with water.

He remembered that 15 farmers would have their grain shocked for a threshing “run.” As a boy, he would sit on the threshing machine with Herman Diersen. “He had the biggest machine around – and at noon he would give me ten cents to crawl inside the machine and clean out the shakers.” (Ten cents in the early 1940s would be worth about $2 in 2025.) That threshing machine, manufactured about 1938 or 1940, could go up to 30 miles per hour, while others only went four to 15 mph. “Top of the line.”

From his poem, “The Farm,” Carl “Cully” Boye wrote:

When threshing was over and

all felt the sun scorch,

We would sip on beer on that front porch.

It was never a pleasure to go

after the cows,

As always they wandered as far

as time allows.

Hard work continued throughout the threshing and hauling to the granary. Another boyhood memory: “Before we got a grain elevator, the guys would carry bags of grain on their shoulders up the steps and through a hole in the floor upstairs and then fill the bin upstairs. Must have been a lot of young guys around to do all this work.”

Threshing was not quite over after the threshing ended. There might be “threshing dust in your eyes, ears, noses and lungs for days.”

Corn was shredded in the autumn. It was cut and then shocked to dry out. Later that fall or in the winter, when they had more time, they would run the corn through a shredder, which would husk the corn, remove the ears and then chop the stalks, the latter being blown upstairs in one of the barns and could be used for bedding.

Source: “A Creek Runs Through Me; A History of the Winnebago Creek Valley in Southeastern Minnesota” by Barbara Scottston and Terry Atherton, 2013.

Photo courtesy of the Houston County Historical Society

Leave a Reply