Around home in Houston County, he was known for his humorous watercolor cartoons. In Europe, his photography helped the United States Army defeat Nazi Germany. George J. Stuber (1922-2020), after graduating from Aquinas High School in La Crosse, learned his craft while employed by Century Photo. Initially a janitor, he had become a manager by the time World War II took him to Europe.

After joining the Army in 1943, and basic training at Fort McCoy, Wis., and Fort Riley, Kans., Stuber became a staff photographer at the Cavalry School at Fort Riley. Following a stint at the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) at the University of Nebraska, he was transferred to the 20th Armored Division, serving as the Division Photographer.

“During maneuvers, I developed a portable darkroom to process photos in the field,” he wrote. “Thanks to Eastman Kodak, I got materials to take photos using Infra Red (infrared) film and lights for night photographs. No one could see the flash from Infra Red bulbs.”

His division was transferred overseas in December 1944. There Stuber built a “truly remarkable” darkroom in a trailer with a portable generator, large enough for both developing and enlarging photographs. The Armored Engineers pulled his trailer behind an armored personnel vehicle, known as a half-track.

He was assigned to take and develop photographs for Counter Intelligence, even taking aerial photographs for the Field Artillery. With his portable darkroom, Stuber could process and have ready two sets of four aerial photos just 30 minutes after landing.

The 20th Armored Division landed in La Havre, France, moved into Belgium and then south into France. They crossed the Danube River, captured Munich and liberated the concentration camp at Dachau. The division was engaged in the Battle of the Rhine through the southern part of Germany, ending up in Salzburg, Austria, when Germany surrendered.

Stuber’s photography consisted of recording training in Europe, pictures of German defenses, V-2 German mobile launch systems, river crossings, prisoners of war, battlefields, concentration camps and flying in L-5 observation planes.

While American troops were moving through the Siegfried Line, a German defensive fortification system along the western border of Germany, Stuber said, “one captain asked me to walk over a field near an emplacement to photograph two dead German soldiers. When I took their pictures, I noticed what looked like many bullet holes in their uniforms. I realized they had landed into one of their own minefields.

“Standing still, I looked around and saw a sign for “German Mine Field.” Within six feet of me, I could see the three prongs of an S-mine. Carefully taking my hunting knife that my mother had sent me, I prodded the ground ahead of me using my Engineers Mine technique to get back to the road. It took me five minutes to walk out to get those pictures, one hour to get back.”

Going through Frankfurt, Germany, one of the Allied Brockway Truck drivers backed into a distillery, knocking out a brick wall with the crane and disconnecting a 5,000-gallon tank of brandy. He loaded the tank onto the truck and brought it out to the American camp in the woods. One officer mistakenly thought it was wine while most of the soldiers enjoyed the unexpected refreshment.

Stuber had to help his inebriated tentmate back into the front of their tent, but his buddy managed to sneak out the backside. While Stuber was bringing him back again, Bedcheck Charlie (an enemy night-time aircraft) destroyed their tent and foxhole. “So, there must be some good in drinking,” concluded Stuber.

“For weeks after, whenever I went to get water for my darkroom, I had to smell the Jerry cans (5.3-gallon steel containers) to make sure it was water and not booze.”

During the Battle of Munich, Stuber recognized friends from Fort Riley when the cavalry drove into Munich and were welcomed by the citizens. But there was a different greeting when the 20th Tank Battalion crossed a prairie towards the West Point or military educational institution for the German SS paramilitary troops. Stuber described it as large buildings with a brick wall about 6-8 feet tall.

“The Germans blew holes in the wall and using their famous 88’s, shot and disabled quite a few of our tanks. They also had trenches and tunnels to protect their positions,” continued Stuber. “We did win, but it was scary to the troops. Some tanks were hit at such close range that the shells went in and out before exploding.”

The next day, Stuber’s job was to take pictures throughout the area. “Going into an open tunnel between trenches, I crept inside to get a better photo. As I did, the sun came out and sunlight shone through an opening. I noticed a silver glint. It was a trip wire booby trap. If I had backed into it to get a better shot, I wouldn’t be writing this.”

After Germany’s surrender (V-E Day, May 8, 1945), Stuber was busy with division photo projects, including pictures of USO celebrities, Hitler’s hideout and famous castles. His division returned to California and was scheduled to go to Japan where the war raged on. Stuber was home on furlough when word came the war in the Pacific was over as well (V-J Day, September 2, 1945).

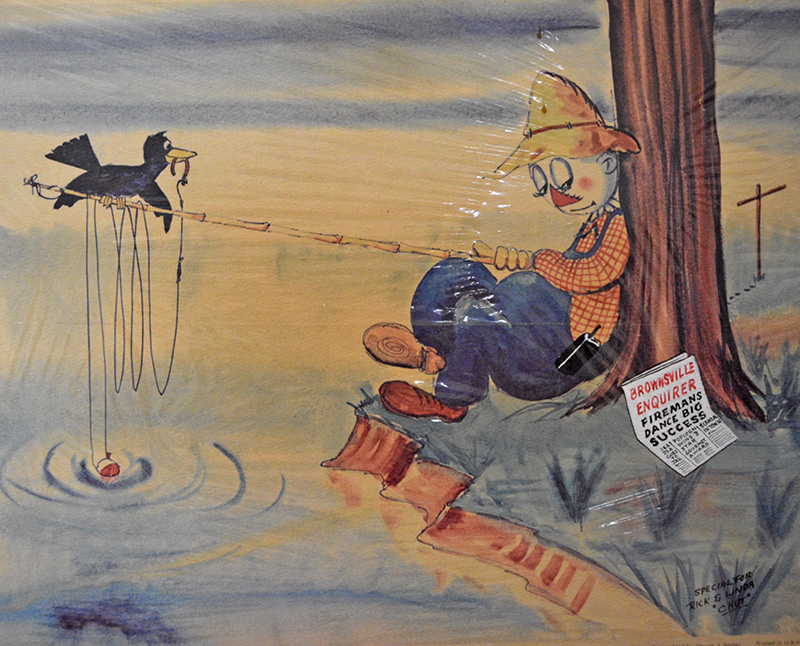

On the G. I. Bill, he attended art school in Chicago and eventually started his own business, Advertising Art Service. In 1960, Stuber and his father-in-law bought a 100-acre tree farm south of Brownsville, where he loved to paint, especially remembered for his humorous scarecrow prints. His death in 2020 came about two months before his 99th birthday.

Sources: “George J. Stuber’s Time in Service and Some of His Interesting Episodes in World War II,” by George J. Stuber of Brownsville, Houston County Veterans Memorial, 2000; obituary of George J. Stuber, 2020

Leave a Reply