Final part six of a series

It’s said that Isadora Duncan, the world-famous dancer, wrote a letter to Bernard Shaw saying, “You and I should have a child who would inherit my beauty and your brains.” The whiskered playwright is reported to have replied. “Miss Duncan, I am flattered, but just suppose the child should inherit your brains and my beauty.”

Sister Agnes Hafner included a few pages of jokes when she published a collection of articles about her childhood on a Houston County farm during the Great Depression of the early 1930s.

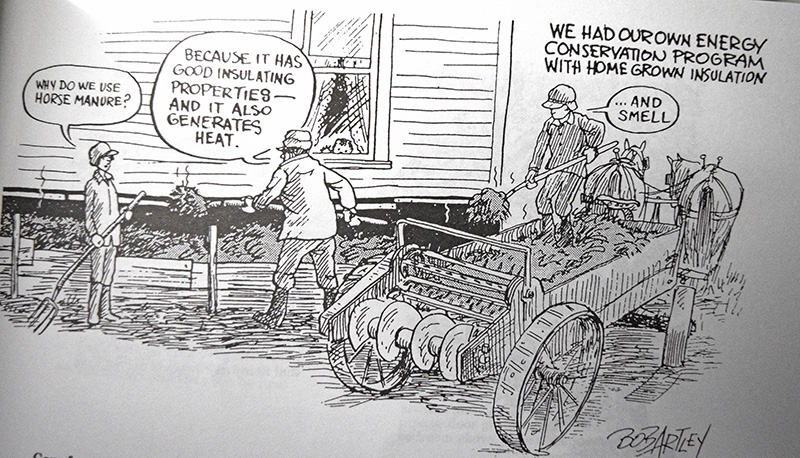

Houses were also without insulation in the walls, but often, there was home-produced insulation. Manure was spread along the side of homes for insulation and a few winter-months later, farmers would spread the same manure on the fields for fertilizer. One merchant humorously advertised, “We guarantee our manure spreaders, but we don’t stand behind this product.”

Any rooms that received wind from two or three sides, sometimes called “show” rooms, had an advantage during summer but would be closed off during winter. In the Hafner farmhouse, such a first-floor room had a Persian rug and several pieces of beautiful hand-carved furniture, which was characteristic of that era. Her pioneer grandfather was skilled at designing and hand-carving “fancy furniture.” This formal room was off-limits for the children.

Above it on the second floor, the “cold room” had a spare bed and a closet, which was the hiding place for gifts from Santa.

A row of clothes hooks were found near outside entrances and in bedrooms. Farm folks had very limited wardrobes with only or two sets of Sunday clothes. Therefore, closets were not usually built into bedrooms. Girls always wore skirts. Snow pants were permitted in winter, but they had to be removed at school along with coats and stocking caps.

Basements had dirt floors and were lighted only by one or two small windows. Some families kept butter and milk there to keep cool. Families had a cistern for drinking water, but some had a second cistern where rainwater was kept and where milk and butter was placed in a “shotgun cream can,” which was lowered and raised by a rope into the cool water. Sometimes, jello was “set” in a submerged cream can.

Farm homes had no indoor plumbing, except the pipes from the kitchen sink into the back yard. An outhouse was also known as a “back house” or “two-holer.” When indoor toilets were invented, they were simple “with a pipe leading into the chimney for fumes from the circular outside area that contained a big inner pail with a handle.” It was a welcome improvement over a cold, drafty outhouse where Sears Roebuck catalog pages served as “tissue.”

The living room was used by everyone for many different activities. There was a toy box in the Hafner home. Tinker toys were popular. With no electricity, there were wind-up toys. “Wind up the frog and watch him hop across the floor.” A wind-up train engine could pull a few box cars on a circular track. Agnes concluded that the train set was really for the parents, who told the children it was for the youngsters. “Otherwise, why would parents not allow children to run it without parents being there to thoroughly enjoy it?”

During the late 1920s, news and entertainment had arrived through a battery-powered radio, featuring such popular songs as “When it’s Spring Time in the Rockies” and “Red River Valley.” Every evening, a radio comedian entertained for about an hour, a treasured time that was set aside whenever possible.

In many homes, an open attic under the roof was used for storage and accessed by narrow winding stairs. Above some inside doors were transoms, small windows, which could be opened by two chains, one on each side, for ventilation.

Home was the most common site for medical attention, such as colds or flu. “Mothers were the best doctors in the world and the cheapest,”opined Sister Agnes, “with their homemade tallow, mustard plaster, Mercurochrome and Vicks Vapor Rub, or possibly a Watkins product, like liniment.”

Trips to the doctor were only for serious concerns, such as a barefoot child stepping on a rusty nail. But Dr. Archie Skemp’s home visits were certainly welcome when he arrived to deliver babies or treat an ailing senior citizen or a seriously ill child. “He loved to do it and all loved to see him come,” Sister Agnes emphasized.

Laughing gas was the common anesthetic for surgery. Agnes recalled her surgery on a toe, after which she indeed awoke laughing.

Most people also died at home, and after embalming at the mortuary, the body was returned to home until the day for the funeral. Neighbors and friends brought casseroles and helped keep an all-night vigil and if needed, care for the children. “Children experienced death in a beautiful way as the culmination of life,” wrote Sister Agnes. “Even the little ones were in on everything.”

Farm children were familiar with death and funerals, including processions with a cross made with sticks for backyard funerals for pets. “It brought closure.”

Despite the economic trials of the Great Depression, Sister Agnes concluded, “Life in the early ‘30s was a happy life for children. Parents struggled to make ends meet, but they never told their children, ‘We are poor or deprived.’ Somehow, parents mentally rose above their circumstances, trusted in God through family prayer, which was common in many families and provided a loving, happy home life.”

Another chuckle from Sister Agnes: Two little nuns driving along a country road ran out of gas and stopped at a farmhouse. The farmer said, “I have some gas in my the barrel but nothing to put it in.” Also being nurses, the nuns found a bedpan in the car trunk. As the farmer was pouring gas into the car, a trucker stopped. His eyes popped! “Now that’s what I call FAITH!”

Sources: A series of guest columns published in the Houston County News, (La Crescent, Minn.) were later published in a book, “Life on the Farm in the 1930s,” by Sister Agnes Hafner, FSPA, 2004. The cartoons by Bob Artley were originally published in the Worthington (Minn.) Daily Globe, and later in his book, “Memoirs of a Former Kid,” 1978, and again in 2004 in Sister Hafner’s book.

Leave a Reply