By Sally Ryman

Rushford Historical Society

Native American mounds in the Driftless region are generally massive earthen effigy mounds that are concentrated on high bluffs and ridge crests overlooking rivers. If you’ve been lucky enough to watch “Decoding the Driftless,” you’ve seen them photographed from the air. Created by various Native Americans hundreds to thousands of years ago, these mounds are unique in all the world. Many still exist, but the Rushford Mounds have mostly been reduced to a historical narrative.

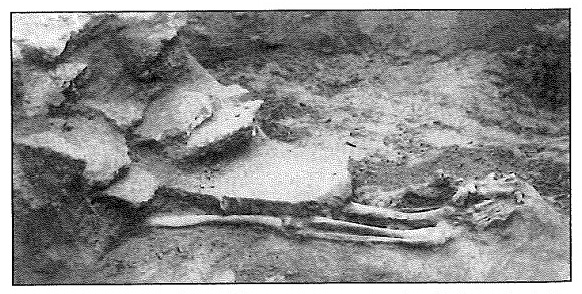

In 1884, there were six mounds on Magelssen Bluff along the central ridge of a Magelssen Bluff salient. Mounds 1, 2, 3 and 4 were round; mounds 5 and 6 were elongated. The Rushford mounds were unusual because they were rock burials with slabs of dolomite and limestone used as a surface covering and to cover the remains inside the mounds. (see pictures)

By 1884, mounds 1, 2, 3 and 5 had been opened and mound 4 was substantially destroyed. The University of Minnesota excavated four mounds July 3-10, 1935. Looters had dug into the center of the mounds, but they had not reached the burial pits where archaeologists discovered four skeletons and two complete bowls:

Mound #1 contained an infant’s skeleton estimated to be three months old based on dental development. The baby’s ribs showed signs of unhealed infection. Mound #2 contained two individual burials. The first skeleton was a 40- to 50-year-old adult male that showed signs of arthritis, cysts, and healed infections. The second skeleton was also a 40-50-year-old male, about 5”7” to 5”9” tall with signs of disease, lesions, and an infection at time of death. The second skeleton had half of teeth abscessed prior to death. Mound #3 contained a 17- or 18-year-old 5’4” male skeleton and a complete bowl. Mound #4 was virtually destroyed prior to 1935; however, they uncovered badly charred bones which might be a sign of cremation, although that wasn’t conclusive. Mounds #5 and #6 were not excavated; it is unclear why.

The skeletons showed that dental and physical health compromised as they aged. For instance, the adolescent didn’t have any tooth loss, while the two adults had lost the majority of their teeth and showed signs of arthritic degeneration.

In 1935, Archeaologist Wilford believed the bowls were of Oneota origin. The Oneota lived AD 1100-1500 across southern Minnesota. However, Archeaologist Wedel disputed this in 1954, identifying the pots as more akin to Middle Mississippian pottery rather than Oneota.

Communications in 1993 from the U of M’s Archaeology Department indicated that human bones and associated burial material was to be returned to the ground through the “Minnesota Native American Reburial and Repatriation Project.” The Native American community does not want anyone not directly related to the project to know the dates and locations of the reburial, so we don’t know where the remains found in Rushford are now.

Sources: 1993 letter from David M. Hayes, University of Minnesota Department of Anthropology; The Aborigines of Minnesota – Rushford Mounds; paper by Kathleen Blue; Minnesota’s Indian Mounds and Burial Sites: A Synthesis of Prehistoric and Early Historic Archaeological Data by Constance M. Arzigian and Katherine P. Stevenson, 2003 by the Minnesota Office of the State Archaeologist; Decoding the Driftless documentary

Photo courtesy of U of M