Many southeast Minnesota settlers in the late 1800s had direct contact with or at least observed local Native Americans, most notably the Winnebago tribe. Marlene Meiners wrote her grandfather would barter with skunk hides for chickens. The Indians made baskets, which they sold for $1 or $2.

The great “Indian scare” did not involve those mostly-peaceful Winnebago neighbors but only the Sioux who were far away. The 1862 Sioux uprising in western Minnesota alarmed settlers throughout the upper Midwest, all the way to Lake Michigan according to the 1919 History of Houston County. Although the Sioux did not get anywhere close to Houston and Fillmore County, the fear of their arrival was a great disruption.

It was a dry and smokey August, and word spread from horsemen traveling east that the Indians were advancing and were burning everything in their path. Having heard the Sioux were near Spring Grove, most of the settlers in Wilmington Township fled with what possessions they could carry toward Lansing, Iowa. But their flight was halted when they heard that C. F. Albee and A. Sherman had ridden on horseback to Spring Grove and learned there was no imminent threat. The fugitives returned home, but losses were substantial for those who had turned their cattle loose into the grain fields.

Many settlers near Caledonia erected a mostly-log fort, which they called Fort Ridgely. In case their homes would be burned, they hid their furniture in the woods.

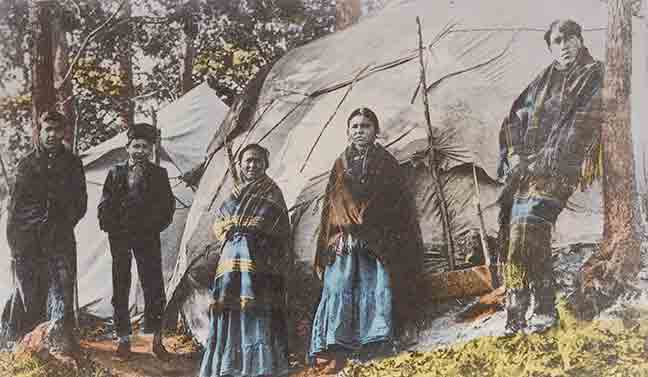

Photo courtesy of the Houston County Historical Society

David Moore recounted a story from his great grandmother, who moved to the Money Creek area about 1860. Shortly after the 1862 Sioux Uprising, a small band of Winnebago were seen crossing the valley towards Money Creek. The settlers became alarmed and prepared to defend their settlement. But a spokesman from the band was sent ahead into the town to assure everyone that they posed no threat as they were merely passing through to a campground on the Turkey River in Iowa.

Decades earlier, through 1832 and 1837 treaties, the Winnebago had previously lost their ancestral homes in Wisconsin to move in 1840 into a 40-mile-wide strip (the Neutral Ground), located mostly in Iowa, but included a small wedge of Fillmore and Houston Counties in Minnesota.

In order to prevent the unhappy Winnebago from returning to their Wisconsin homelands and to protect them from the influx of settlers moving west, especially whiskey traders, Fort Atkinson was established on the Turkey River. In an effort to civilize the Winnebago, a mission and school were built near the fort along with a farm for agricultural education.

With white settlers still moving west, the stay of the Winnebago in the Neutral Grounds was short-lived, and they were relocated to Long Prairie in Minnesota in 1848. They were dissatisfied from the start without the bountiful hunting and fishing to which they were accustomed along the Mississippi River. It was a low-lying area, beset with fever, and they found themselves an uncomfortable buffer between the warring Chippewa and Dakota Sioux. The Winnebago gladly accepted lands along the Blue Earth River in 1855.

While living along the Blue Earth, the Winnebago were persuaded to build homes, plant crops and even wear white man’s clothing. Some were persuaded to send their children to school, but missionaries found few converts to white man’s religion.

Life on the Blue Earth Reservation ended with the Sioux uprising in 1862. Although the Winnebago had remained neutral in the conflict, there was enough anti-Indian sentiment in the aftermath that forced their removal to Dakota Territory in 1863. Here they remained until 1865 when they were given lands in northeastern Nebraska. The Nebraska Reservation is still in existence, but over the years, many Winnebago made their way back to their original homelands and burial grounds in southeast Minnesota and western Wisconsin. A few families might never have departed back in 1848.

During summer, Winnebago families would frequently go back to the reservation in Nebraska to visit family members. There might also be trips to Wisconsin areas near Black River Falls and Wisconsin Dells to visit and pick berries. However, in autumn, they were back trapping and hunting in the Mississippi River bottoms.

They could be found living among white settlers in small family bands near the towns along the Root and Mississippi Rivers. They established seasonal camps and homes in areas around Hokah, Reno, Caledonia, Money Creek and Houston.

About 1910-12, a band of approximately 20 Winnebago, led by White Cloud, settled in Money Creek Township on the Anton Forsyth farm, taking up residence in an abandoned barn near the mouth of Money Creek. Hunting and fishing provided food along with the abundant wild onions in the river bottoms. Animal hides could be tanned for clothing in addition to fabric purchased in town. As well as food, berries and nuts were used for dyes. And every now and then, Mr. Forsyth would give them a cow or pig. In autumn, they were permitted to gather in his garden and potato patch.

White Cloud’s band moved to Dakota, Minn., in 1917. After his death, White Cloud was brought back for burial along the Root River near Houston.

Typical of the era, most bands of Native Americans were relatively independent, choosing to be separate from their white neighbors. Living in abandoned buildings or the more traditional lodges, they would occasionally make trips to town to purchase or trade for needed supplies and to sell their handcrafted wares.

The Winnebago were known for their handcrafts, especially baskets. Along the river bottoms, the white ash tree provided weaving material. When the sap was running, the trees were cut down, and entire logs were left to soak in a pond or spring for several weeks. Then they could be pounded with wooden sticks to separate the annual growth rings into thin sheets. Strips were then cut for weaving.

Sources: Caledonia Pride articles, including those by David Moore, Marlene Meiners and Mike McCarthy. Also, the Caledonia Centennial Journal, 1854.

Leave a Reply