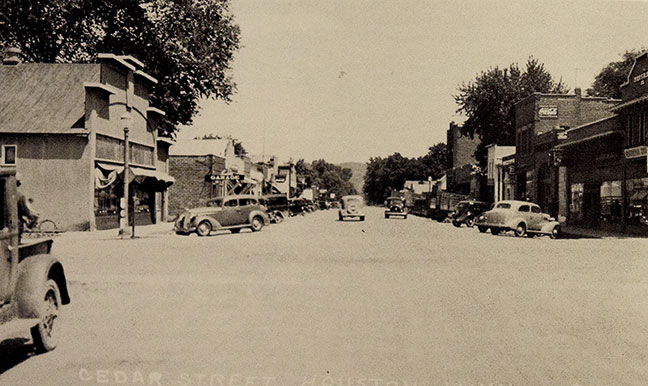

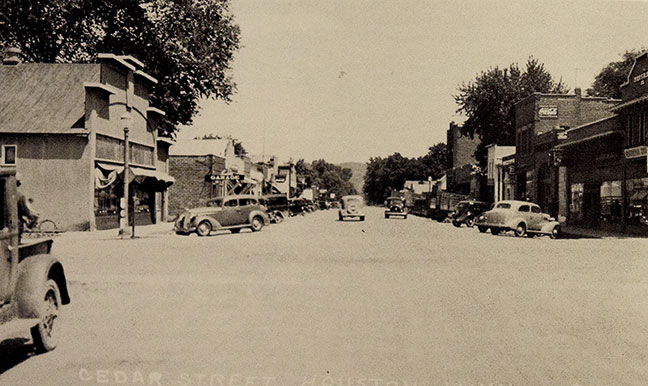

Photo courtesy of Houston County Historical Society

Electricity came late to the village of Houston, maybe conjectured Julsrud due to a lack of labor and/or materials during World War I. The main electric lines came from Caledonia through Badger Valley in 1918, the year the war ended.

The city gas plant had deteriorated to the extent that many citizens had installed their own lighting systems. Some were using carbide lights at home. Carbide (a compound of carbon with an electropositive element) came in 50-pound drums, which were lowered into a hole in the back yard. Water dripped over the crystals, forming a gas that flowed through pipes into the house.

Julsrud said her family still had gas lights at home. When the pressure got so low that it was difficult to read or sew, they lit the gasoline lamp. “We opened a valve on the side of the gas container after we had filled it and pumped pressure into the chamber. We used a pump much like a bicycle tire pump. Then, wheeee! – we had lights so bright it almost hurt our eyes.”

Soon after electricity came to town, it was surely the shortest speech delivered in Houston when mayor John Redding said, “Let there be light.” He then pulled a switch and lights illuminated streets in Houston, followed by applause. It was about 1919 when the mayor, accompanied by the village council and two men from the light company arrived in a truck at a grassy plot on South Sheridan Street for the festive occasion.

From then on, there were street lights at every street corner, including residential neighborhoods. The lights hung in the middle of the intersections, not bright by later standards. Bright moonlight was considered sufficient, so the street lights were not turned on at all on brighter moonlight nights.

Street lights were turned off at 11 p.m. In those days before radio (much before television), there was not much enticing folks to stay up late. The evening newspaper arrived on the 8 p.m. train, and paperboys delivered promptly. Merle Barton and Condee Anderson delivered those papers during much of their youth. After the newspapers had been read, houses went dark, one by one.

If there was a light on after 10 or 11 p.m., it meant either there was a party in progress or there was an illness, with Dr. Fischer or Dr. Onsgard, Sr. making a house call. Julsrud thought doctors saw more patients in their homes than they did in their office. “Parties that lasted far into the night were really something to talk about.”

After radios were present in every home, everyone stayed up to listen to Cedric Adams and the 10 o’clock news on WCCO. Sometimes, Adams aired his broadcast from small towns all over Minnesota. Once, after broadcasting from his old hometown, Adrian, in southwest Minnesota, he flew back to the Twin Cities. The following night he reported that he had seen lights go out in homes right after the broadcast as flew over them.

Adams once broadcast from the high school gymnasium in Houston. Before the news, there was a program featuring local talent, including a singing trio of Maynard Nelson, Lucille Olson Flom and Lylas Ronnenberg Floss.

The first radio in Houston was owned by Guy Steves, a longtime telegrapher and train station agent. Julsrud was among a group who were back home for Christmas from their college or their first teaching jobs and joined the church choir for the holiday season. After a rehearsal at Steves’ home, Mr. Steves offered everyone an opportunity to take turns putting on the earphones to listen to this amazing technology.

“It was a wonder to us. We heard people talking from all over the United States to (a station in) Schenectady, New York… It must have been about 1923 or ’24.” She recalls the first radios having three dials on the front, which needed constant adjusting to keep the sound clear. “Just a few years later came the loud speaker and just a flip of the switch and there were the voices. About 25 years later came television.”

After electricity came to town, the first electric appliance purchased was the electric flat iron. “It was a gift from heaven,” Julsrud proclaimed. Before that acquisition, irons were heated on the kitchen range with the fire maintained even when the summer temperatures approached 90 degrees in the shade. The kitchen itself could feel like an oven.

“Ironing was more work than washing, and it took all day. Everything needed ironing in those days, and I mean everything!”

Those first electric irons were very heavy, weighing close to eight pounds. It was believed that weight as well as heat contributed to effective ironing – getting material smooth. That proved to be a misconception when irons became much lighter.

There were washing machines before electricity. On the side, there was a large wheel, which was turned by hand. Julsrud’s grandfather sat beside the washer all Monday morning, turning that wheel around and around, wash load after wash load. The clothes then went through a hand wringer into two rinses before being hung on the clothes line.

Not long after electricity came to Houston, grandfather went to town and bought a new electric washer as a gift for Julsrud’s mother and grandmother. But her granddad may have benefited most.

At that time, during World War I, her grandfather had just sold a load of hogs from the farm. Prices were so good that he paid for the new washing machine with the price of one hog, $45. “He never tired of telling the story that he bought a brand-new electric washing machine for just one hog.”

That machine served the family for many years until being replaced by a new Speed Queen.

Source: 1993 book, “Remembering Old Times, Houston During the Post Card Era,” by Ingrid Julsrud

Leave a Reply