Part two of a series

It was September 1932 when Mathilda (Mrs. Knute) Lee of Spring Grove traveled by bus to Rochester to meet with Minnesota congressman Paul Quale from Benson, the top regional official of the Red Cross, C. M. Roland, that organization’s Assistant National Director of Disaster Relief, Henry Baker, and other volunteers from other Minnesota counties. Her paid expenses included $2.55 for bus fare, 75 cents for lunch and another 25 cents for ”incidentals.”

Clara Mathilda Glasrud Lee had been appointed Houston County Roll chairman of the 1932 Red Cross membership drive. The national organization set a goal for the county to enroll 700 members.

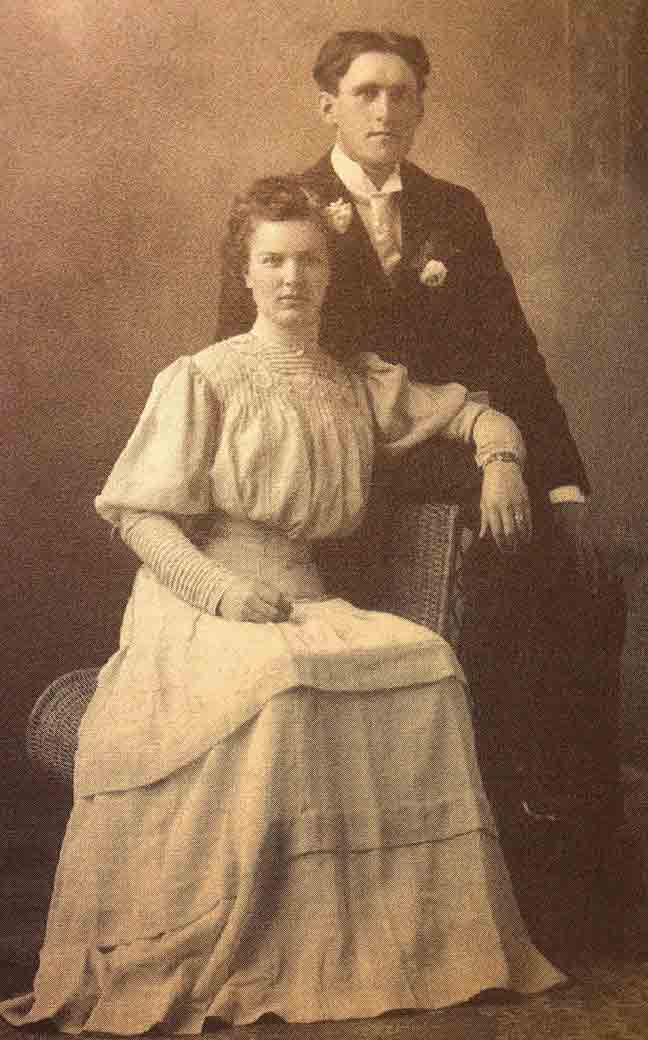

Photo courtesy of “Mathilda’s Journey”

Support for the Red Cross was strong because of its work during World War I, followed by disaster relief during postwar years. And about a dozen years after the war ended, the disaster at hand was the Great Depression that lasted about 10 years after the stock market crash of 1929. Over seven decades after that, Mathilda’s son, Robert E. A. “Bob” Lee, wrote, “I can almost re-live with her the excitement and stimulation of her sudden immersion in a process aimed at helping unemployed and destitute citizens of a new and sudden poverty.”

At that orientation at Rochester, she learned the American chapter of Red Cross was first organized in 1881, just two years before her own birth, and finally chartered in 1905, only a year before her marriage. Mathilda must have felt a kinship with the organization, which like she, had “grown and matured over the same half-century,” before being brought together in southeast Minnesota by the Great Depression.

While in Rochester, Mathilda had been able to visit her cousin Inga Qualey, who had worn the emblem of the Red Cross on her nurse’s uniform during the war. Mathilda, recalling the nursing service provided by the Red Cross, had written in her notebook, “If you develop nursing services well, it strengthens all other parts of the service.”

The officials at the meeting in Rochester emphasized the role of the Red Cross as a citizen response to the economic hardships that affected so many. The notes she took that day included traveling around the county to La Crescent, Hokah, Caledonia, Eitzen, Wilmington and Riceford. “She prepared well, knowing that she would need to answer questions, give talks, write articles for newspapers” and along with county chapter chairman Henry Blexrud, be a spokesperson for the county. “I remember how proud we were,” continued her son Bob, “when she went with Blexrud to La Crosse to speak over radio station WKBH. She called that ‘quite an event.’ She told me she wrote the talk herself.”

She spoke that day, along with Pastor Clarence Lee of Caledonia, as part of the regular Red Cross drive every autumn. Mathilda spoke first and later realized she must have taken a minute or two longer than planned because Pastor Lee didn’t get much time.

Mathilda learned she would be supervising the distribution of both food and clothing as well as raising funds. She was to recruit, organize and supervise a volunteer chairman in each community and village in the county. One would be her sister-in-law, Lillian (Mrs. William C.) Glasrud in Black Hammer Township while dentist Dr. Harold Lovold served in Spring Grove.

Each week local newspapers would publish a list of those donating 50 cents or a dollar or on rare occasions, $2. Bob related that his mother was determined to meet the goal of enrolling 700 members in Houston County. Raising funds would not be easy, because money was scarce. However, in this case, people knew that the recipients of any generosity would be citizens in their own community, their own neighborhood or nearby farm – instead of hurricane or flood victims from elsewhere in the nation.

With the annual drive beginning on Armistice Day, November 11, 1932 (commemorating the end of World War I, now known as Veterans Day), Lee planned a meeting in Caledonia on October 26 where she and Blexrud would explain to the community chairmen the distribution of flour and cotton cloth, according to guidelines from the national organization.

A carload of flour would arrive at the train station and be stored at the C. J. Sylling elevator. Flour was only for qualified families, which had applied and been approved. With the approval form, families could receive one 49-pound sack or for a large family, two sacks at a time. A family could obtain a maximum equivalent of one barrel of flour to last 90 days. Flour could not be given to an institution, and transients would be referred to county welfare workers.

Other food supplies were added from time to time, such as oranges and grapefruit. There was clothing and lengths of cloth, which like the foodstuff had been purchased by the federal government and given to the Red Cross for distribution to needy families. Mathilda wrote, “Congress holds us responsible.” She shouldered that responsibility in Houston County.

The distribution center for clothing and food in Spring Grove was the dining room in the Lee family dwelling.

To be continued.

Source: “Mathilda’s Journey” by Robert E. A. Lee, published in 2000