By Lee Epps

Her oldest sibling, 14-year-old Walter, was understandably disappointed when she was born. After all, he already had five younger sisters. But young Adelia Schumacher would be tomboy enough to catch and shag the baseballs cousin Julius “swatted when Walt honed his pitching skills.” Adelia (Schumacher) Sievert (1913-2001) left a written account of growing up on a farm on South Ridge in Houston County in her book, No Regrets; A Memoir.

Her first bed was a clothes basket. “They were made of sturdy fiber, not plastic throwaways. They were handy, not too big and not too little and had good handles.” Placing a pillow inside made a “dandy bed” for a newborn. To prevent winter floor drafts in an early 1900s farmhouse, the clothes basket bassinet was placed on two chairs.

The youngest would at some point graduate into the rocking cradle built by Father, sturdy enough to last through a steady progression of Schumacher siblings.

After supper during winter, the family would gather around the living room wood-burning heater. Mother sat in a large reed rocker with the youngest child in her lap while the next youngest sat on a baenklein (small bench) made by Father. As they comfortably watched flames flicker though the isinglass windows in the door of the stove, all joined in singing hymns in German, such as “Mude bin ich, geh’ zur Ruh,” (Tired I am, I go to rest).

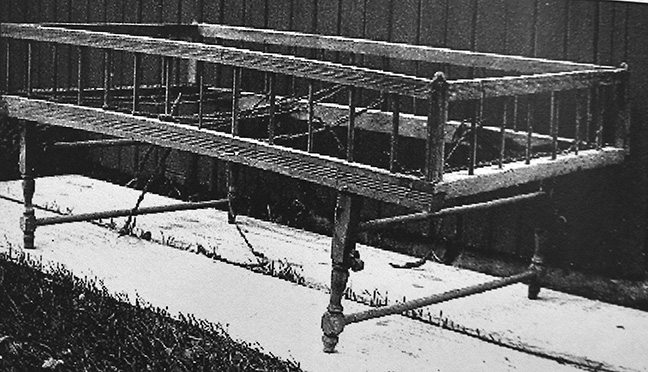

At bedtime, it was “a hop, jump and skip” up the stairs to the children’s chilly bedroom. The youngest slept on the trundle bed, which was rolled beneath the standard bed during non-slumber hours. The legs folded up and down underneath, and when folded up, small wheels on each leg made it was easy to roll. The bed spring was metal mesh, similar to fine chicken wire.

Beneath several woolen quilts, only a nose might protrude near the “chinner.” A chinner was a strip of white fabric about 24 inches wide which was basted to overlap the head end of a quilt. It prevented the edge of the quilt from being soiled by chins, noses and other facial features.

Beneath the bed was the chamber pot for middle-of-the-night calls of nature. Adelia wrote, “The low position made comfort nonexistent, but the convenience made it tolerable.”

Meanwhile, downstairs in the parents’ bedroom, the cradle was placed next to mother’s side of the bed. Mother had a soft cloth looped over her arm and onto the cradle. When she heard a whimper, she would move her arm a bit to rock the cradle. “Papa disliked hearing a crying baby,” Adelia noted. “So, Mama’s arm grew strong and sturdy with her nightly pull on the cradle.”

Her parents’ bedroom was on the main floor with three bedrooms upstairs. One was for Walt, the oldest and for a long time, only brother. One was called the guest bedroom, usually unused, unless some of the young adult siblings were back home. A long bedroom had two double beds and the trundle. “We could easily sleep five, maybe six, if three of us crowded together,” recalled Adelia. There were no bedroom closets, just hooks for the few clothes they owned.

Straw tick mattresses were used on the larger beds. As soon as threshing was completed each autumn, the old straw was scooped out of the mattresses, which made of ticking (a strong cotton fabric), looked like giant pillows. The ticking would be washed and dried before being carried over to the stack of straw, where many hands participated. Several hands would hold open the seam at the top of the ticking while others grabbed fresh straw and stuffed it in. “It took Mama’s strong arms to reach into the corners and fill in all the empty spaces. By the time we were finished, the mattress looked like a tummy much too full.” The seams would be basted (sewn) shut, and finally, men carried each mattress into and up to the bedrooms.

“Those first few nights trying to sleep on this mound of straw were like trying to sleep on top of a huge pumpkin.” The sleeper in the middle had no problem, but one on the outside might end up on the floor before morning. The smaller children would need a boost to make it on top. There would surely be “crinkle or crackle” sounds from the mattress during the night, but the sleepers had been too busy and too tired to miss any well-deserved sleep.

There were plenty of chores for everyone, including young sisters Adelia and Marie, who often worked together. When charged with churning during pleasant weather, they took turns churning butter outside beneath the trees. At other times, the young churners “turned the wheel” in the kitchen.

The girls washed and dried the glass lamp chimneys, but filling them with kerosene was a task for someone older. Brick dust was used to polish forks and knives. These implements were not “silverware,” but instead easily-stained metal with wooden handles. Dust was scraped from an old red brick into a small pile. The girls dipped a damp cloth into the dust and rubbed the forks and knives until they shined, “Our fingers got all grubby from red brick dust and black metal stain. This was, understandably, an outside job.”

Hauling wood for the cook stove and heater was a critical cold-weather, childhood chore. Their father limited their trips between the woodpile and the back door by constructing a rack for their sled and wagon so wood could be piled higher.

There were times when the children created a little fun to make chores “less tiresome.” During summer, Adelia and Marie were responsible for scrubbing the kitchen chairs with soap and water. When they carried them outside onto the back lawn, they lined them up in rows like church pews or school benches. The girls conducted church or school for their favorite dolls. Their pupils, Mamie and Efa, were rag dolls, which had detachable faces that could be removed and washed.

Sources: the book, No Regrets; A Memoir by Adelia Sievert, 2022

Photo submitted

Leave a Reply