By Lee Epps

Third in a series

It was at first a disappointment as well as an inconceivable surprise. Later, it provided welcome albeit unexplained enjoyment – cool relief during summer heat for area visitors and annual snowball fights during Fourth of July celebrations. It was a longtime source of amazement when it was “cool” to be in Brownsville, Minn.

It took about 120 years, but a Houston County phenomenon would finally be explained. St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter Earl Chapin stumbled onto a story near Brownsville. About 1861, water had frozen in a well (or mine) shaft and had not melted all year. Nearby, there was cold air coming out of an opening in the hillside. After serendipitously running across and writing about the “Brownsville ice pit” in the summer of 1947, Chapin contacted the University of Minnesota for a scientific explanation but had no luck. Remembering hearing about ice caves in Idaho, he wrote a state university geology department there. “The savant was of no help; he replied that neither I nor the camera saw what we thought we saw, or words to that effect.”

Beginning to question what he had seen 20 years earlier, Chapin returned to Brownsville in 1967. “It’s a conundrum that has bugged me since I first stumbled on to it 20 years ago,” he wrote in his second article about Brownsville, when he realized he had not lost touch with reality after all. There was still frost or ice in the vertical shaft and cold air around that opening in the hillside. After all he could learn – or not learn from the experts – it appeared to him that if the opening in the hillside was cleared and the debris dug out of the pit, the ice in the pit would “perpetuate itself.”

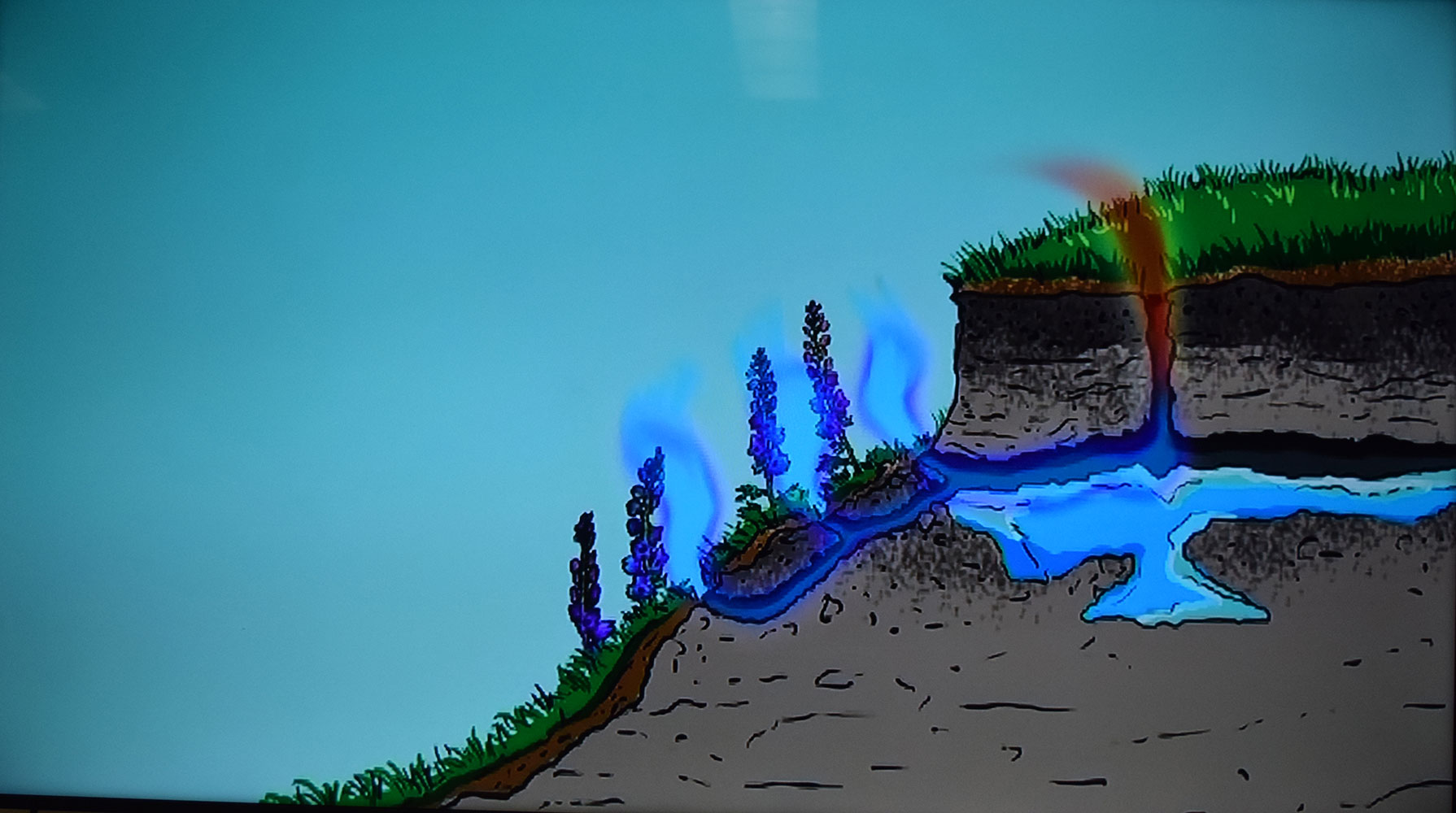

Unfortunately, Chapin (1910-1973) did not live to see science explain the mystery in the early 1980s. Even though it may have seemed strange to dig horizontally into the hillside, It was thought both the well shaft and the other opening had been man-made. But as science would reveal, that other opening emitting cold air during the summer was natural, albeit rare. An “algific talus slope,” also known as a “cold-air slope,” is a small, isolated microclimate involving a blufftop sinkhole above a subterranean ice cave with a vent through a sloping hillside.

Algific (pronounced with a soft “g” sound, ahl-JIFF-ik) means “cold-producing,” and talus is a mass of rocky fragments, loose rocks (in this case porous limestone) that have tumbled down a rocky hillside. An algific talus slope requires three elements: (1) a steep north or northeast-facing slope, sheltered from summer sun, (2) strewn with rocky debris full of air pockets connected to a deeper network of open spaces or caves within the hill plus (3) a sinkhole on a bluff or ridge above the cave.

Caves are often described as having a constant temperature. Niagara Cave in Fillmore County, Minnesota, maintains 48 degrees. However, in an algific talus slope, the much colder and denser winter air outside the hillside is drawn through vents in the talus (fractured rock) into the cave, replacing warmer air on cave floors where flowing water and atmospheric humidity is turned to ice.

In summer, if above the cave, there is a sinkhole which funnels air and rainwater into the ice cave – the air flow reverses. Warm air is drawn down from the sinkhole atop a bluff to be cooled in the ice cave and then flows out as cold air through vents in the limestone. In summer, the area around these vents on north-facing hillsides can be as much as 40 degrees cooler than the surrounding area. A thermometer can record below-freezing temperatures of such outflowing air.

About 1861, Chris Gerhard’s manmade vertical shaft (well or mine) near Brownsville was evidently sunk close enough to such a cold-producing microclimate that inflowing water froze as it did in an adjacent ice cave.

According to editor and writer Gemma Tarlach, “In winter, the same system keeps the area around the vents warmer than the rest of the slope because the hill’s internal respiratory system holds a stable temperature, within a range of about 40 to 50 degrees Fahrenheit, year-round. That narrow range of temperatures on the slopes is why Ice Age relic species can persist at those sites, including plants such as northern monkshood and golden saxifrage, both listed as threatened, and a variety of ancient snails, most famously the endangered Iowa Pleistocene snail, which was thought extinct until a researcher rediscovered a small population at an algific talus slope in Iowa’s Bixby State Preserve.

“Researchers and conservationists are racing to protect these unique sites from a variety of threats,” added Gerlach. “But they acknowledge that their best efforts may not be enough in the face of climate change.”

“Once it’s gone, it’s gone forever,” said Tim Yager of the Upper Mississippi River National Wildlife and Fish Refuge. “You will never recreate those conditions that have been here for thousands of years.”

Algific talus slopes are extremely rare worldwide, but not unusual in the Driftless Area of southeast Minnesota, southwest Wisconsin, northeast Iowa and the far northwest corner of Illinois. At first, thought to exist only in this driftless area in the upper Midwest, other algific talus slopes have been identified in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia. The Driftless Area Magazine says the upper mid-west Driftless Area contains more than half of the world’s algific talus slopes.

Driftless regions are those where glaciers did not extend during ice ages and flatten the landscape. These non-glaciated regions lack characteristic glacial deposits – sand, gravel, clay – known as “drift.” These areas are thus “drift-less.”

The upper Midwest Driftless Area is uniquely a topographical island, surrounded by areas that were covered by glaciers, although not simultaneously. The resulting geology features exceptional variety with steep hillsides, narrow valleys, world-class trout streams, bluff prairies (goat prairies), sinkholes and subterranean caves – plus ancient holdovers: effigy burial mounds, ocean fossils and 1,000-year-old rock drawings.

Sources: Decoding the Driftless, 2018 documentary; Mysteries of the Driftless, 2013 documentary; “The Ice Age Persists in the Upper Midwest, Where the Hills Breathe” by Gemma Tarlach; “The Driftless Area in Northeastern Iowa is home to several Algific Talus Slopes” on The Nature Conservancy website; National Cave and Karst Research Institute website; Britannica.com. Thanks to Jeff Kueny, Geography and Environmental Science, University of Wisconsin – La Crosse. Thanks to Chris Kirkpatrick, Mississippi Valley Conservancy.

Photo submitted

Leave a Reply