Part two of a series

It cost 25 cents to ride the train from Freeburg to Caledonia. The train would pick you up wherever you were. Rural students could take 18-cent rides to high school in Caledonia. The train provided transportation from Caledonia to Little Miami with its the well-water swimming pool and tavern. But that all ended on June 16, 1946.

It was a beautiful, sunny Sunday with healthy crops in the field on the family farm in Crooked Creek Township of Houston County. However, by midday, it became hot and almost unbearably sultry, according to young Houston County farmwife Lucille Pohlman. Wind and storm clouds moved in, followed by rain, lightning and thunder. The electricity went out, leaving Lucille, husband Wilfred and month-old baby Jan Lee in total darkness except for flashes of lightning. “Our home and buildings were on higher ground,” said Lucille, “but as we looked up the valley to the south, we could see flood waters from hill to hill when the lightning flashed.”

“We were not getting that much rain in the valley,” Wilfred said, “ … hardly enough rain to run off a tin roof that night.” However, Caledonia and adjoining Mayville Township were deluged, and the Crooked Creek Valley was receiving the water.

An estimated eight to 11 inches of rain fell around Caledonia, where rainwater ran off the hard streets, down Wiebke Hill next to the soon-to-be destroyed railroad tracks and then south down County Road 32. Omar Goetzinger was driving to Caledonia for a date and barely made it up Wiebke Hill against the shocking flow of water coming toward him.

Highway and railroad crossings sustained massive damage and erosion as did pastures and gouged-out farm fields. According to resident Eldor Wunnecka, most of the hills were pastured, resulting in considerable runoff. Floodwater continued down the valley, joined by runoff from ditches and gullies until spilling into the already flooded South Fork of Crooked Creek.

Photo courtesy of the Root River Soil and Conservation Service.

That South Fork and North Fork converged at the Pohlman farm, where in the darkness, the young couple went to bed about 10 p.m., warily uncertain of what they would see at sunup. Morning revealed flattened oats and alfalfa fields. What had been knee-high corn had been washed away or leaning over with leaves in the mud. “Creek crossings were washed away, and creek banks badly eroded with deep holes in the land,” recounted Lucille. “Whole trees, washed out roots and all and laying hither and thither. Mud and silt covered all the pasture lands and fields. Fences were all gone.”

Cleaning and fixing up would take time and backbreaking labor throughout the valley. Still without electricity, the Pohlmans milked cows by hand and turned the cream separator by hand as well. Grandpa Pohlman came to stay for more than a week to add his hands for the milking and separating. Where corn had survived, small hand sickles and scythes were used to cut corn leaves out of the mud, so the plants could stand upright again. Trees, brush and trash had to be pulled off the farm fields and pastures. Fences had to be replaced.

Edward Colsch said some farm buildings were found over a mile away. It took five years to replace the damaged buildings that remained. The farmhouse was raised two feet with jacks while repairing basement walls.

Flood water had swept through the farmhouse basement of Theodore Schwartzhoff. The garden, crops and many small buildings were gone. All the crop fields up South Fork Valley were devastated, and the creek had changed channels in many places.

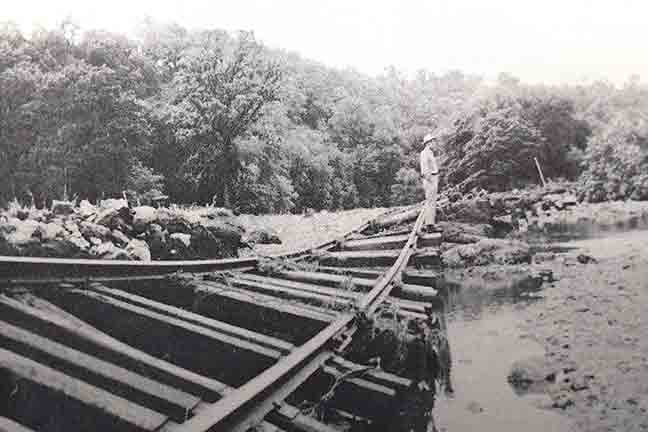

Nearby, a large iron railroad bridge had fallen into the creek as had the township bridge. Most of the highway was washed away, and railroad tracks and ties had been swept off their bed.

Freeburg was so inundated with mud and water that many still refer to it as the Freeburg Flood. Much food was destroyed at Graf’s Store and Post Office, which was inundated with three-and-a-half feet of water. Freeburg resident Bob Fisch recounted how a buggy and baby suddenly began to float in the Hanke Store before everyone escaped.

Fisch remembered the roar of water going through town that night. “It was like a six-foot wall of water all at once,” he told an area newspaper. He said cars started to float away from the bar, Little Miami. “Clarence Lichtenberg tied a rope around himself and waded to one vehicle to rescue a man.” Fisch, one day before his 18th birthday, had intended to take the train to Caledonia the next day to register for the draft. But he had to find other transportation.

Wilfred Pohlman said more than 30 bridges between Caledonia and Freeburg were “wiped out.” Tracks that were swept across one road were wrapped around big white pine trees, which likely saved the farmhouse of Ted and Mary Schwartzhoff.

Across the road, a railroad boxcar rested on isolated tracks. The road bed had to be repaired before a steam locomotive engine was able to retrieve the stranded boxcar.

Bob Bissen surmised the loss of the tracks may have caused floodwater to rush into his home where the basement was completely filled and 10 inches of water standing in the kitchen. Bissen described how water had sliced through some of the steel rails, calling it “just a clean break.” The sound of meowing led to discovery of a kitten atop the battery beneath the hood of his relocated 1941 Ford.

The railroad depot at Freeburg was swept off its foundation and came to rest a half-mile away. The post office and depot never returned. The railroad did not repair the tracks on the east end of the Preston-Reno branch. Passenger and freight service between Caledonia and Reno, dating back to September of 1879, ended with the flood of 1946. There were no more train rides from Caledonia to Little Miami. The pond there was filled with mud, and the attraction never reopened. Could anything be done to prevent this occurring again?… to be continued

Sources: Written recollections at the Houston County Historical Society and a 2006 article by David Heiller, published in the Caledonia Argus.